Sophia Perovskaya on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya (russian: Со́фья Льво́вна Перо́вская; – ) was a Russian Empire

Perovskaya participated in preparing

Perovskaya participated in preparing

Just before her trial, she wrote in a letter to her mother:

Perovskaya, along with the other conspirators were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging.

She was the first woman in Russia sentenced to death for terrorism.

On the morning of 15 April

Just before her trial, she wrote in a letter to her mother:

Perovskaya, along with the other conspirators were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging.

She was the first woman in Russia sentenced to death for terrorism.

On the morning of 15 April

The Beauteous Terrorist and Other Poems

b

Sydney Electronic Text and Image Service

* Moss, Walter G., ''Alexander II and His Times: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky''. London: Anthem Press, 2002. Several chapters on Perovskaya. (availabl

online

* Croft, Lee B. ''Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich: Terrorist Rocket Pioneer.'' IIHS. 2006. . Content on Perovskaya, including her father, mother, and her unmarked burial. *

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

and a member of the revolutionary organization ''Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya ( rus, Наро́дная во́ля, p=nɐˈrodnəjə ˈvolʲə, t=People's Will) was a late 19th-century revolutionary political organization in the Russian Empire which conducted assassinations of government officials in an att ...

''. She helped orchestrate the assassination of Alexander II of Russia

On 13 March Old Style], 1881, Alexander II of Russia, Alexander II, the Emperor of Russia, was assassinated in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, Russia while returning to the Winter Palace from Mikhailovsky Manège in a closed carriage.

The assa ...

, for which she was executed by hanging.

Life as a revolutionary

Perovskaya was born inSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, into an aristocratic family who were the descendants by the marriage of Elizabeth of Russia

Elizabeth Petrovna (russian: Елизаве́та (Елисаве́та) Петро́вна) (), also known as Yelisaveta or Elizaveta, reigned as Empress of Russia from 1741 until her death in 1762. She remains one of the most popular Russian ...

. Her father, Lev Nikolaievich Perovsky, was the military governor of Saint Petersburg. Her grandfather, Nikolay Perovsky, was a governor of Taurida

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the ...

. She spent her early years in the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, where her education was largely neglected, but where she began reading serious books on her own. After the family moved to Saint Petersburg, Perovskaya entered the Alarchinsky Courses, a girls’ preparatory program. Here she became friends with several girls who were interested in the radical movement. She left home at the age of sixteen over her father's objections to her new friends. In 1871–1872, together with these friends, she joined the Circle of Tchaikovsky

The Circle of Tchaikovsky, also known as Tchaikovtsy/Chaikovtsy (russian: Чайковцы), or the Grand Propaganda Society (russian: Большое общество пропаганды, ''Bolshoye obshchestvo propagandy'') was a Russian literar ...

. In 1872–1873 and 1874–1877, she worked in the provinces of Samara

Samara ( rus, Сама́ра, p=sɐˈmarə), known from 1935 to 1991 as Kuybyshev (; ), is the largest city and administrative centre of Samara Oblast. The city is located at the confluence of the Volga and the Samara (Volga), Samara rivers, with ...

, Tver

Tver ( rus, Тверь, p=tvʲerʲ) is a city and the administrative centre of Tver Oblast, Russia. It is northwest of Moscow. Population:

Tver was formerly the capital of a powerful medieval state and a model provincial town in the Russian ...

, and Simbirsk

Ulyanovsk, known until 1924 as Simbirsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Ulyanovsk Oblast, Russia, located on the Volga River east of Moscow. Population:

The city, founded as Simbirsk (), w ...

. During this period, she received diploma

A diploma is a document awarded by an educational institution (such as a college or university) testifying the recipient has graduated by successfully completing their courses of studies. Historically, it has also referred to a charter or offici ...

s as a teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. whe ...

and a medical assistant

A medical assistant, also known as a "clinical assistant" or healthcare assistant in the USA is an allied health professional who supports the work of physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other health professionals, usually ...

.

A prominent fellow member of the Circle of Tchaikovsky, Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

, said the following of Perovskaya:

In 1873, Perovskaya maintained several conspiracy apartments in Saint Petersburg for secret anti-tsarist

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states ...

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

meetings that had not been sanctioned by the authorities. In January 1874, she was arrested and placed in the Peter and Paul fortress

The Peter and Paul Fortress is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740 as a star fortress. Between the first half of the 1700s and early 1920s i ...

in connection with the Trial of the 193 The Trial of the 193 was a series of criminal trials held in Russia in 1877-1878 under the rule of Tsar Alexander II. The defendants were 193 socialist students and other “revolutionaries” charged with populist “unrest” and propaganda again ...

. She was acquitted in 1877–1878. Perovskaya also took part in an unsuccessful attempt to free Ippolit Myshkin, a revolutionary and a member of Narodnaya Volya. In the summer of 1878, Perovskaya became a member of ''Zemlya i Volya

Land and Liberty (russian: Земля и воля, Zemlya i volya Zemlia i volia; also sometimes translated Land and Freedom) was a Russian clandestine revolutionary organization in the period 1861–1864, and was re-established as a politica ...

'', was soon arrested again, and banish

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

ed to the Olonets Governorate

The Olonets Governorate or Government of Olonets was a '' guberniya'' (governorate) of north-western Imperial Russia, extending from Lake Ladoga almost to the White Sea, bounded west by Finland, north and east by Arkhangelsk and Vologda, and sou ...

. She managed to escape on her way to exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

and went underground.

As a member of ''Zemlya I Volya'', Perovskaya went to Kharkov

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

in order to organize the liberation of political prisoners from the central prison. In the fall of 1879, she became a member of the Executive Committee and later a member of the administrative committee of ''Zemlya i Volya''. Perovskaya propagandized among students, soldiers, and workers, took part in organizing the ''Worker's Gazette'', and maintained ties with political prisoners in Saint Petersburg. In November, 1879 she took part in an attempt to blow up the imperial train

A royal train is a set of railway carriages dedicated for the use of the monarch or other members of a royal family. Most monarchies with a railway system employ a set of royal carriages.

Australia

The various government railway operators of A ...

on its way from Saint Petersburg to Moscow. The attempt failed. On her return to Saint Petersburg she joined ''Narodnaya Volya''.

Assassination of Alexander II

Perovskaya participated in preparing

Perovskaya participated in preparing assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

attempts on Alexander II of Russia

Alexander II ( rus, Алекса́ндр II Никола́евич, Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ftɐˈroj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ; 29 April 181813 March 1881) was Emperor of Russia, Congress Poland, King of Poland and Gra ...

near Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

(November, 1879), in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

(spring of 1880), and Saint Petersburg (the attempt that eventually killed him, 1 March 1881). She was the closest friend and later the wife of Andrei Zhelyabov

Andrei Ivanovich Zhelyabov (russian: Желябов, Андрей Иванович; – ) was a Russian Empire revolutionary and member of the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya.

After graduating from a gymnasium in Kerch in 1869, Zhelyab ...

, a member of the executive committee of ''Narodnaya Volya''. Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing attack, with the group of four bomb-throwers - Ignacy Hryniewiecki

Ignacy Hryniewiecki or Ignaty Ioakhimovich Grinevitsky). (russian: Игнатий Гриневицкий, pl, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, be, Ігнат Грынявіцкі; — March 13, 1881) was a Polish member of the Russian revolutionary societ ...

, Nikolai Kibalchich

Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich (russian: Николай Иванович Кибальчич, uk, Микола Іванович Кибальчич, sr, Никола Кибалчић, ''Mykola Ivanovych Kybalchych''; 19 October 1853 – April 3, 188 ...

, Timofey Mikhailov

Timofey Mikhailovich Mikhailov (russian: Тимофе́й Михайлович Мих́айлов; — 15 April 1881) was a member of the Russian revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya. He was designated a bomb-thrower in the assassination of ...

, and Nikolai Rysakov

Nikolai Ivanovich Rysakov (russian: Николай Иванов Рысаков; – 15 April 1881) was a Russian revolutionary and a member of Narodnaya Volya. He personally took part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia. He threw ...

. However, when Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, Perovskaya took the role.

The night before the attack, Perovskaya helped assemble the bombs.

On Sunday morning, 13 March Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

], the bomb-throwers gathered at the group's flat on Telezhnaya Street. At 9–10 AM, Perovskaya and Kibalchich each brought two missiles.

Perovskaya would later relate that, before heading to the Catherine Canal, she, Rysakov and Hryniewiecki sat in a confectionery store located opposite of the Gostiny Dvor, impatiently waiting for the right time to intercept Alexander II's cavalcade. From there they parted ways and converged on the canal.

In the afternoon, the Tsar was returning by Catherine Canal in his carriage after watching the weekly military roll call. Perovskaya, by taking out a handkerchief and blowing her nose as a predetermined signal, dispatched the assassins to the canal.

When the carriage was close enough for an attack, Perovskaya gave a signal, and Rysakov threw the bomb under the Tsar's carriage.

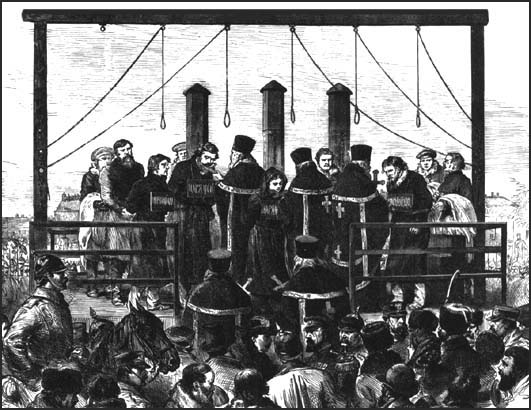

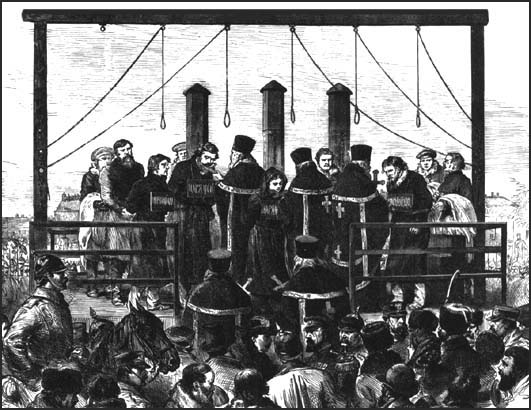

Hanging

Rysakov was captured, and while in custody, in an attempt to save his life, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and the tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya, along with others, on March 22. Rysakov established the identity of all prisoners. Although he knew many of them only by their party pseudonyms, he was able to describe the role they each had played. Just before her trial, she wrote in a letter to her mother:

Perovskaya, along with the other conspirators were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging.

She was the first woman in Russia sentenced to death for terrorism.

On the morning of 15 April

Just before her trial, she wrote in a letter to her mother:

Perovskaya, along with the other conspirators were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging.

She was the first woman in Russia sentenced to death for terrorism.

On the morning of 15 April Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

], the prisoners were transported to the parade grounds of the Semenovsky Regiment, where the execution was set to take place. They were all dressed in black prison uniforms, and on their chests hung a placard with the inscription: "Regicide". Perovskaya, along with Mikhailov and Kibalchich, was placed on a cart that was drawn through the city by a pair of horses.

The correspondent of the London Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (f ...

estimated that the execution was attended by a hundred thousand spectators. When priests ascended the gallows to give the last rites, the convicts almost simultaneously approached them and kissed the crucifix. Once the priests withdrew, Zhelyabov and Mikhailov approached Perovskaya and they kissed each other good-bye. Perovskaya had turned away from Rysakov.

Four other Pervomartovtsy

Pervomartovtsy (russian: Первома́ртовцы; a compound term literally meaning ''those of March 1'') were the Russian revolutionaries, members of ''Narodnaya Volya'', planners and executors of the assassination of Alexander II of ...

, including Zhelyabov, were hanged with her.

Legacy

Three decades after her death, Perovskaya would become the inspiration for the Japanese feminist Kanno Sugako, who was involved in a 1910 plan toassassinate

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have a ...

the Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

. Kanno was also executed by hanging.

In 2018 the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' published a belated obituary for Perovskaya.

In literature

*Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. He has ...

was inspired by her to write the poem, ''The Beauteous Terrorist''. Reproduced in full in The Beauteous Terrorist and Other Poems

b

Sydney Electronic Text and Image Service

* Moss, Walter G., ''Alexander II and His Times: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky''. London: Anthem Press, 2002. Several chapters on Perovskaya. (availabl

online

* Croft, Lee B. ''Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich: Terrorist Rocket Pioneer.'' IIHS. 2006. . Content on Perovskaya, including her father, mother, and her unmarked burial. *

Jan Guillou

Jan Oskar Sverre Lucien Henri Guillou (, ; born 17 January 1944) is a French-Swedish author and journalist. Guillou's fame in Sweden was established during his time as an investigative journalist, most notably in 1973 when he and co-reporter Pet ...

uses Perovskaya in his book ”Men inte om det gälle din dotter” (”But not if it concerns your daughter”) as an example of how changes in political situation can alter the perception of a person between being a terrorist and a freedom fighter.

See also

* 2422 Perovskaya *Women in the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 saw the collapse of the Russian Empire, a short-lived provisional government, and the creation of the world's first socialist state under the Bolsheviks. They made explicit commitments to promote the equality of men ...

References

Bibliography

* * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Perovskaya, Sophia Lvovna 1853 births 1881 deaths Executed people from Saint Petersburg Narodnaya Volya Russian Empire prisoners and detainees Internal exiles from the Russian Empire Female revolutionaries Executed revolutionaries Executed people from the Russian Empire Narodniks Executed women from the Russian Empire People executed by the Russian Empire by hanging 19th-century executions by the Russian Empire Revolutionaries from the Russian Empire Prisoners of the Peter and Paul Fortress